Is Gerrymandering Impossible with the Representation Amendment?

What if you could arrange the congressional districts in your state so the political party of your choice wins a majority of House seats every election for a decade?

You don’t prevent anybody from voting. You simply group voters so the party that will get the majority of votes in each district is known beforehand. Winning is a sure thing!

Would you be tempted if that power were entrusted to you? The people who draw congressional district boundaries after each census have that power. They can influence the outcome of elections for years into the future. Can you trust them?

Setting congressional district boundaries to ensure an outcome in an election is called gerrymandering. As a voter, you should be aware it affects the quality of your representation in America.

Centuries of Political Manipulation

Political parties have manipulated district boundaries to gain an upper hand in elections for centuries. The modern day Democrat and Republican parties are no different. But party affiliation is not the only reason to draw district boundaries to control the outcome of an election. Other reasons include race and personal vendettas.

Gerrymandering is how a political party ensures it holds a majority of House seats when it lacks a majority of voters in a state or portion of a state. Seems rather unfair. But what does the Representation Amendment do to help minimize gerrymandering? It turns out the Representation Amendment could be very effective against gerrymandering.

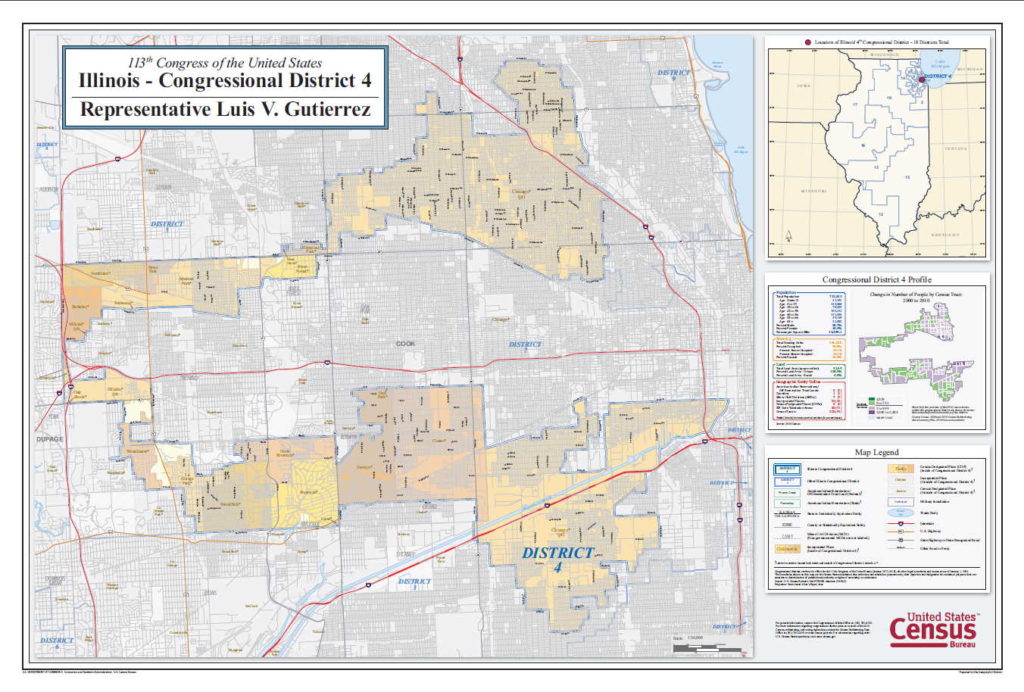

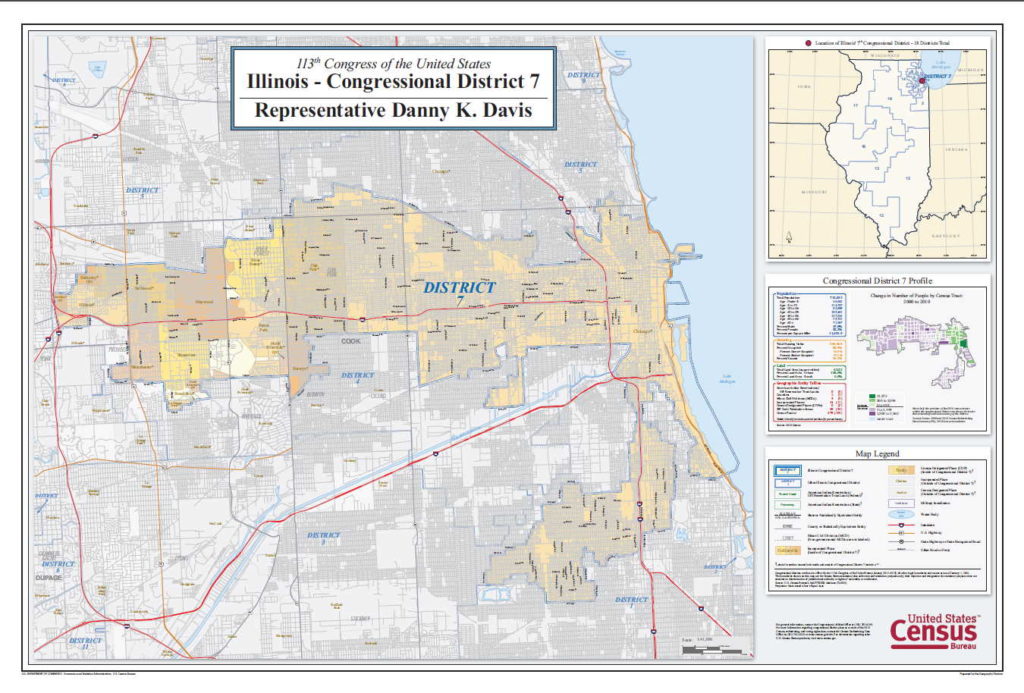

The United States Census Bureau provided the above picture (PDF). The shaded section of the map shows the 4th congressional district in Illinois. This district was chosen as an example based solely on its shape. The odd shape comes from the way the 4th district wraps around the 7th district on three sides.

Examine the intricacies of the borders of the 4th district. Somebody went to a lot of trouble selecting residents street by street. You have to zoom into the picture quite a ways to see the narrow corridor connecting the north and south bodies of the district.

Whether the objectives of the people who designed these congressional districts were noble or unapologetically political, the end result is the same. It looks like somebody wanted a specific outcome in an election. Otherwise, why not combine the 4th and 7th districts and just split them down the middle, only taking care to keep an equal number of people in each district?

A district is still gerrymandered even if done with good intentions. And if somebody can gerrymander a district with good intentions, somebody else can gerrymander a district with bad intentions. But the intent of the people who designed district 4 are irrelevant to this article. What matters here is how the Representation Amendment makes designing convoluted districts like the 4th Illinois congressional district far more difficult.

With the Representation Amendment...

According to the U.S. Census, 712,813 people reside in this 52 square mile district. The Representation Amendment sets a maximum of 30,000 people per House district. The 4th district would split into approximately 24 House districts under the amendment rules. That means 24 people will represent the neighborhoods in the 4th district currently represented by a single individual.

To capture the same level of voting power in the “Representation House” as one member of the “Legacy House” has today, the people who design congressional districts must craft 24 districts that elect 24 people who would vote exactly the same as the one representative does today. Not possible. Same party? Maybe.

Even in a heavily Democrat or heavily Republican district, once it is broken down 24 ways, you’ll likely get at least one district that elects a member of the opposition or a third party. Read about Representation for the 49% and The Representation Amendment Gives You the Viable Third Party in other posts on this site.

Gerrymandering Small Districts

Now widen your view from the 4th district in particular to a map of the whole of Chicago. First, clear all the existing district boundaries from the map. Second, mark the boundaries of new districts containing up to 30,000 people throughout the city of Chicago. (The 4th district is 52 square miles, which cut 24 ways comes to approximately 2 square miles each, just to give you an idea of the size per district.) Finally, try to gerrymander these tiny districts.

Gerrymandering this many tiny districts with no great distinction between neighborhoods along their borders hopefully becomes more effort than it’s worth.

Each block in a city like Chicago can have its own unique characteristics but the residents of a two square mile district will still be fairly similar in culture, income, ethnicity, ideology, class, and so on. That means that the person elected by the people of that tiny district will be very similar to themselves.

Differences might be obvious from district to district, but along the borders between districts, the distinction might be minuscule. How is one to tweak the boundary of a district when the people on the next street over aren’t so different from the people in that district? And if you add the people on that street, which border street in this district do you transfer to a different district to maintain the balance of population in each district?

Deciding on What is Fair

People are going to argue over how best to define a congressional district. Are district boundaries to be as square as possible, following natural boundaries where necessary? Is the goal to stuff as many “like” people into each district? How do you define “like people”? Is it good enough to simply state, “The 30,000 people in this district chose to live in close proximity in neighborhoods not separated by artificial or natural barriers.” and allow them to elect a person of their choosing?

It’s probably impossible to make everybody happy when drawing district boundaries. Somebody will see the outcome as unfair based upon their preferred criteria.

Conclusion

The Representation Amendment generally provides better odds of states forming unbiased congressional districts than our current system. The sheer number of districts involved makes fixing the outcome of districts more difficult, as each change results in a cascade of changes to other districts. Politicians will try, of course. But they only get away with it so long as the people of your state allow it.

Gerrymandering will exist anywhere people hold elections. No system is perfect. However, we as a people can implement a system that discourages gerrymandering, if only by making the effort not worth the reward. The Representation Amendment gets us closer to that goal.